The Many Waves of Afrocentric and Natural Hair ~ Part 2 in Our 3-Part Series

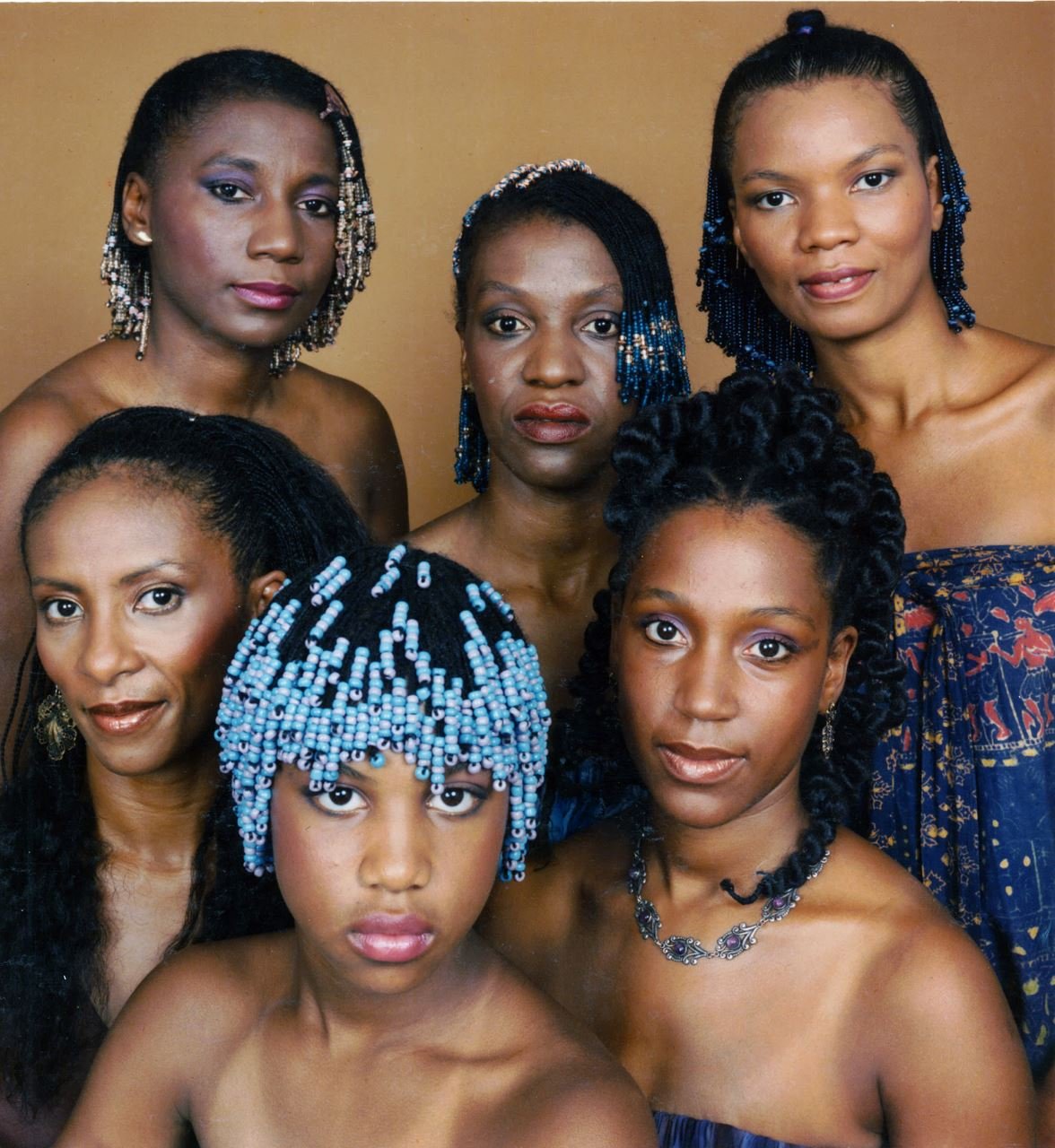

An array of braided styles by Anu Prestonia - circa 1982

Those who came after my peers and me in the mid-80s, were from the fourth wave, characterized in part by single-braid and cornrow extensions with human hair. There were sometimes hundreds of long and thin braids attached to the wearer’s hair individually (later called “box braids”). Women proudly wore these styles, which allowed for abundant versatility and creativity in styling.

Fourth-wave stylists included, Diane Bailey, Deborah Hare-Bey, Talia Wajeed, Cecilia Hinds, Miriam Counsel, Anita Hill Moses, Susan Peterkin, and Mishon Mishon, who also created the silky dreads. The styles with human hair were more readily accepted as they could emulate the look of straightened hairstyles. Despite this, Black women in many industries were still being told that they could not wear their hair in braids to work. The acceptance of that was still decades away. In the interim, Diane Bailey and Tulani Kinard were at the vanguard of New York state legislation that allowed natural hair styling to be grandfathered into cosmetology. Years earlier, I had attended the Robert Fiance School of Cosmetology and acquired my cosmetology license in 1985.

Those Amazing Locs!

Another fourth-wave hallmark was the advent of locs and silky dreds. Initially, dreadlocks, as they were known, were most famously worn by Rastas in Jamaica and other Caribbean Islands, or by those in Africa going through spiritual initiations or from certain tribes such as the Baye Fall in Senegal. Indeed, indigenous people worldwide have worn their hair locked, like the ancient Hindu Sadhus, and even Japanese people living in the bush.

But the fourth-wave of natural hair in the U.S. was the first time dreadlocks, which became known as locs, (dropping the dreadful part of the name) could be achieved by going to a salon to have your hair professionally groomed. I learned how to groom locs when I worked for a few months at the famous Brooklyn-based Kinapps Barber Salon, the creation of Ademola Mandela. Then, Dr. Joanne Cornwell took locs to the next level when she patented a style called “sister locks,” tiny natural hair locs created with a hook tool.

Ultimately, locs became a sensation for both men and women! Black people were expressing themselves more freely than ever before, and able to grow their natural hair long, very long, with locs.

Goddess Braids by Khamit Kinks commissioned by Essence Magazine - Stylist Tamasa Titley

It is interesting to note that before the Senegalese invasion, customers had to book an appointment with my salon two to three months in advance. The presence of the Senegalese stylists in various communities allowed more women to have hair appointments at an easier and faster pace, simply because there were so many of them. However, their presence did not shake me, since in addition to fabulous hair-styling, my salon offered customer care of both hair and scalp. And in keeping with my standards, the first Senegalese stylist who worked for Khamit Kinks, Ngone Sow, came from a family of three generations of skilled hairstylists. So, clients would mention to me the many African-owned salons they passed to get to my salon.

Next Wave Evolution

In the era of MTV that followed, stylists at other salons cultivated straight weaves, which became very much in vogue, influenced by women dancing in music videos swinging long, straight or wavy hair weaves. Khamit Kinks did not offer straight weave styles, because we were always about “keeping it kinky.” Instead, we offered textured weaves with names like bush baby (see photo at right).

Then, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, I noticed a resurgence of naturals — or afros revisited — when young college-age women began calling my salon seeking styles that didn’t include braids, twists, or extensions. They wanted to wear their hair out, loose, and naturally textured with the use of products. Many of these new, young “naturalistas” had the same thing in common. They had grown up having their hair processed straight, and had no idea what their natural hair looked or felt like, or how to style their own hair. They began researching, then took to blogging, vlogging, and attending and being featured on the digital university platform called YouTube!

Natural Textured Hair by Khamit Kinks

Third Wave Trends and Transitions

When I arrived at Howard University in 1976, the most popular braiding styles, which had come out of Maulana Ron Karenga’s US Organization in California, were very tiny cornrows with tiny beads, as well as cornrows with extensions. I began braiding hair professionally in 1977 in Washington, DC, at Shelton’s Salon. At that time, a fellow Howard student named Shay Wafer, (today a noted theater executive director) taught me how to put in my first extensions. This was an extraordinary gesture, since, back then, no one – but no one! – wanted to reveal their techniques. Our braiding clients at that time were mostly students, artists, and those involved in the African consciousness movement.

In 1979, I was living in Miami when the movie “10,” launched and brought with it the general public’s awareness of natural hair braiding. The society matrons of Coconut Grove would try to hail me down to braid their hair like the film’s actress, Bo Derek. Notably, it was then that cornrows with beads became more accessible to the mainstream public with the addition of extensions, which allowed women with chemically processed hair to have their hair braided. Human hair extensions also came on the heels of synthetic extension braids, with beads slowly fading out. (The beaded styles at the left were done without extensions.)

These styles became so popular that, at one point, I was traveling between Miami, New York, the Bahamas, and Washington, D.C., to do my clients’ hair. Eventually, I ceased traveling to do hair, and settled in Harlem for several years, braiding client’s hair in a beautiful, leather, vintage barber’s chair I had acquired in Miami. But by 1987, I had moved again and began what became a 35-year Brooklyn and TriBeCa, NY odyssey of professional hair care and styling, founding the Khamit Kinks natural hair care salon which rose to its zenith in the decades that followed.

Other third wave contemporaries were the prolific stylists Fana Smith, Tulani Kinard, Pamela Ferrell, Amazon Smiley, and my former partner, the late great, Ruth Sinclair. I consider the third-wave braiders, including myself, descendants of US Organization braiders, like Malakia Johnson and Nawili Griffin. Then there was Margo Wells, who later sat in the bay window in Vernard Gray’s Maya Gallery in Washington, DC in the mid-70s turning out exquisite styles, as a living, moving, braiding form of art. It was a phenomenon that inspired many of us.

Khamit Kinks Locs Groomed and Styled by Andre Tinnie

It was In the early ‘90s that the hair game changed completely when my salon was featured in Essence Magazine with a style I coined, called goddess braids. Indeed, a version of the image at left, worn by Queen Latifah, was actually featured on the cover. Dana Taber created this style out of Miami, a stylist under the tutelage of Ruth Sinclair. Those who said they would never have their hair braided, ultimately ate those words once they laid eyes on our goddess braids.

The Senegalese Invasion

Senegalese women are known as some of the most fashionable women in Africa, and I dare say, in the world. At the beginning of the early 90s, they came to America sporting uniquely creative hair styles, and began styling hair as a way to make a living. Even before this, Senegalese twists, corkscrews, and Casamas braids had become popular in the mid-80s, following my return from a 1984 trip to Senegal, with some of these styles in tow.

The Senegalese stylists opened storefront salons on nearly every corner of our urban neighborhoods, and became fierce competition for American-born natural hairstylists. They knew how to cut corners to give you a look you wanted at less expensive prices without putting in the same amount of time, volume, and skill. One trick they used was making small braids around the perimeter but then using much larger parting for the rest of the head.

There were professional Senegalese stylists with phenomenal skills, but there was a great gap between them and untrained others who only began braiding once they arrived in the U.S., just to make a buck.

Textured weave by Khamit Kinks stylist, Jahmillah Collier

What emerged next was a movement of women who wanted to have a more knowledgeable and, therefore, intimate relationship with their newly discovered natural textures. They sought out, tested, and blogged about any number of products they were using on their hair, including Anu Essentials natural hair care products. Many who did not know how to manipulate their own natural hair came to us for consultations, big chops, and would line up before the break of dawn for our Black Friday Specials of naturally textured hair. It was an exciting and exuberant time, circa 2007-2013, for natural hair which included many pop-up events, meet-ups, and branding soirees, of which we had a few. Click here to see Part 3 of this series.

Acknowledgements

For nearly a decade of my professional career, I worked alone until Bee Bee Johnson, and Alaka Jones became my first assistants, working in Harlem in the early 1980s. Then later, the many incredible stylists who created the phenomenal styles of Khamit Kinks also came in waves. This list is so long that it's difficult to include everyone, but those who had the most significant impact are as follows:

First Wave (Halsey Street) - Tamasa Tiltley, Rohanna Thomas, Seshua Mandola, and Habiba Ali

Second Wave (Halsey Street) - Ngone Sow, Shelly Toppin, Wendy Toppin, Marva White, and Zauditu Chambers

Third Wave (TriBeCa) - Jahmillah Collier, Thema Taylor, Nicola Augustine, Khady MBaye, Nene Souane, Anta Fall, Andre Tinnie, Greg Nero and Aingeel Tally

Fourth Wave (Gold Street and Atlantic Avenue) - Jennifer Acheampong, Fatoumata M'Baw, Kange Styles

Many thanks to my incredible administrative team, who booked appointments, gave valuable advice, did consultations, and offered love and support - Gemi-Men Taylor, Patricia White, Simeko Hartley, Kalalea Kalalea, and Thaifa Smith.

A special thanks go out to Patricia Warrington, Taeisha Black, and Melody Wells, who held it down to the end.

Click here for Wave 1, 2, and 3.